Video footage of students at some of the nation’s most highly regarded universities and colleges brow-beating and obscenely berating their professors and administrators was eerily reminiscent Chairman Mao’s ‘Cultural Revolution’.

From the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, youthful Red Guards—many of them students—rampaged through China purging schools, universities, government, industry, the military, and the Communist Party of individuals suspected of less than whole-heartedly supporting Mao Tse Tung’s vision for China.

Distinguished men and women from all walks of life—professors, scientists, administrators, soldiers, and Party functionaries—were abused and often physically assaulted while being forced to read lurid confessions to newly-invented sins they had never committed.

The process left a tragic trail of one and a half million dead. Many millions more suffered horrendous persecution. And, sadly, the baleful effects of this hideous period in China’s history still afflict the nation today.

No less sadly, the American students currently engaged in abusing their professors and administrators seem blissfully unaware of the eerie resemblance their ugly behaviour bears to that of the Red Guard during the Cultural Revolution.

Ironically, however, the subjects of their abuse—the instructors, administrators, and educational theorists who have shaped American education over the past half century—have only themselves to blame.

As the philosopher George Santayana observed: ‘Those who will not learn from history are doomed to repeat it.’

And history, along with its companion discipline, geography, have not been taught in America’s schools for many a year. The two subjects are now, theoretically at least, loosely lumped together under the heading ‘Social Studies’.

If ‘Social Studies’ were simply a harmonisation and rationalisation of two closely related subjects, that would be one thing—unnecessary perhaps; excessive, probably; but essentially benevolent in its intent.

When one examines its fruits, however, one can see the results have been anything but laudable. More than 30 years have passed since my daughter asked: ‘Mommy, what did men do during the Revolution?’

Her schoolbooks dealt extensively with how the revolution affected women, Native Americans, and, to a lesser extent, slaves. But the roles of the founding fathers and the fighting men were treated so casually as to virtually ignore them. Things have not improved in the interim.

Burning of the Frigate Philadelphia in the Harbor of Tripoli, by Edward Moran (1829–1901). From Wikipedia.

The problem is that social studies as a subject was conceived neither to teach us history nor to inform students about the world in which they live. Its primary purpose seems to be social engineering—to impart ‘proper attitudes’ and foster ‘appropriate behaviour’.

In short, Social Studies is history and geography bent to the purpose of social engineers.

Why, for example, teach children to locate the continents or the world’s capitals when learning how far flung places are tends to undermine the goal of teaching them to think globally?

Similarly, our self-anointed Solons have expurgated religion from Western history—presumably on the grounds that religion is divisive, or gets in the way of our sex lives, or some other such nonsense.

For example, the organisers of an exhibition on William Shakespeare at England’s National Portrait Gallery assembled all manner of artifacts the Bard may have used in his daily life, omitting only the three that exerted the most vital influence on his writing.

They are the 1558 Book of Common Prayer, Miles Coverdale’s Great Bible, and the Geneva Bible.

In other words, Reformation theology—the hot-button intellectual interest of Shakespeare’s age—was entirely ignored in this exploration of the psyche of a major public figure whose life was dominated by issues of religion.

What, on the other hand, can one expect from people who applaud the notion of excising the role of the Church from the political, social, intellectual, and spiritual history of the Middle Ages—not to mention the Public Square in today’s America?

All this has exceedingly serious implications for the future of our democracy. Not least, it has left America prey—internally and externally—to demagogues, deceivers, and fanatics of every stripe.

One might not like religion or the religiously minded any more than one likes leprosy, syphilis, and the Black Death. But all three played a major role in shaping the foundations upon which our history is laid. And discussion of them should not be suppressed simply because they are distasteful.

Moreover, as Santayana so presciently observed, if we fail to understand the past, it is unlikely we shall understand the present—and this bodes evil for that which is to come.

As it happens, a worrisome failure to understand the past is currently threatening our future. Our government, for instance, still maintains that Islam is a religion of peace, and Islamic resentment against the West is largely fuelled by the devastation inflicted on the Moslem world by the Crusades.

What government does not tell us, however, is that the Crusades were the West’s much belated response to more than 400 years of Islamic savagery.

That First Jihad had destroyed countless thriving Christian communities in North Africa and the Middle East. In the process, it also subjugated all Portugal, Spain, and Sicily, as well as much of France and Italy, to brutal Moslem rule.

Nor do our political masters explain that terrorism, kidnapping, and enslavement have been tools of Islam from its very inception, and that the United States has been a victim of jihadist aggression from the very moment of its independence.

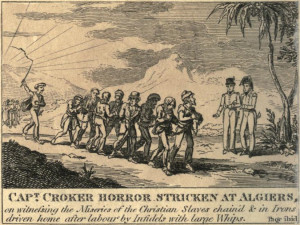

In 1793, for instance, 11 American ships were seized by Barbary pirates—Moslem terrorists operating out of Algiers and Tripoli who kidnapped, enslaved, or held to ransom innocent Christian men, women, and children.

In 1793, for instance, 11 American ships were seized by Barbary pirates—Moslem terrorists operating out of Algiers and Tripoli who kidnapped, enslaved, or held to ransom innocent Christian men, women, and children.

Unable to raise funds to pay the ransom for the crews, the U.S. representative was compelled to borrow from a friendly Jewish moneylender living in Algiers to pay the nearly $1 million ransom.

But this only served to encourage terrorism. Well into the first half of the 19th Century, two thirds—repeat two thirds—of the U.S. federal budget went to paying off the maritime terrorists whose direct descendants today hijack aircraft, bomb, and kidnap on a world-wide scale.

Such knowledge might not encourage people to support current policies that seem largely aimed at placating the Islamic world—rather the contrary, in fact. But absent such an historical perspective, how can they form objective opinions one way or the other? GPH✠

This is somewhat better than usual but the vision is again limited and tendentious. So let us deal with the points in sequence.

(1) Islam means the area of Peace in Arabic, BUT as in the Hebrew Tradition (Shalom), to which it and we are related, that means the peace that comes after a battle, after a striving. The reason that World Governments, Muslim Scholars and Muslims generally interpret this to mean that the striving and war is over and the relative peace across the world is the peace to which Muslims have always striven. Professor Tariq Ramadhan makes the point well, when he asserts that Muslims have more religious freedom in the world at large than they do in Muslim Lands. Further this political stance is one that most Muslims can accept and support.

(2) Yes the Crusades were the Western Christian Response to Muslim aggression using the Furor Normanorum and Muslim methods. Hindus did the same to Muslims in their development of the Sikhs. The Eastern Christians response was peaceable and worked, they tended to buy the Muslims off, but were under no illusions. Manuel II Palaiologos (27 June 1350 – 21 July 1425) was Byzantine Emperor from 1391 to 1425 had been educated by the Muslims. He had a dialogue believed to have occurred in 1391 between him and a Persian scholar and recorded in a book by Manuel II (Dialogue 7 of Twenty-six Dialogues with a Persian) in which the Emperor stated: “Show me just what Muhammad brought that was new and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached.” “God is not pleased by blood – and not acting reasonably is contrary to God’s nature. Faith is born of the soul, not the body. Whoever would lead someone to faith needs the ability to speak well and to reason properly, without violence and threats… To convince a reasonable soul, one does not need a strong arm, or weapons of any kind, or any other means of threatening a person with death…” Wikipedia. Manuel was very effective and travelled West to seek support but to no avail, there was a civil war against the Hussites, and the others felt far away.

(3) There is evidence that some Christian groups assisted Muslims in their conquests, because they were angry with the “Christian” Government, and they thought rightly that Arabs would be cheaper. The “Christian” Government since Constantine had used the Church to impose harmony and obediance, as the Government, of England, Andorra, Monaco, Vatican, Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Iceland, do to this day. “Non Conformists” objected but had no America to flee to, and so joined the Arabs.

(4) Rule of any kind at the time was brutal.

(5) Muslims do enslave, and always have done. Christians had doubts about it from an early time, and many slaves were freed. The United States of America used Slavery down to Modern Times, and the descendents of those slaves still suffer discrimination, violence and death.

(6) As I have explained, the only way forward is to encourage Muslims of good will, and there are many, to believe that they share our peace and that there is no need for public jihad.

I think that Shakespeare lived in a time when the common people were not much enthralled by “theological” debate but must have been dismayed by the demolition of local religious fondations in order to pay State bills. His references are to the outer forms of religion and not the inner content, and this would have been the level of concern in the local Tavern, which is where Shakespeares works were performed. I am not aware of any phrases in Shakespeares works that show borrowing from the Elizabethan Book of Common Prayer or the Bishop’s Bible. He did not belong to that world.