Liturgical fashions change over the years—just like any other fashion. Seventy years ago, for example, it was fashionable for celebrants to say the liturgy as fast as they reasonably could—on the grounds that one makes fewer mistakes when words are read quickly.

It’s a reasonable enough hypothesis, but, like any other fashion, there were always folks who took things just a tad too far. A parson I knew years ago used to boast he could say the 1662 Eucharist in less than 15 minutes. He did so every Sunday, but I doubt that a majority his flock truly understood a word he uttered.

Things are rather more loosey–goosey nowadays. But that’s not necessarily a virtue. Far too many clergymen today are tempted to personalise their mode of celebration way beyond the point of self–indulgence.

Few clergy have ever followed the rubrics to the letter. But it is worth remembering while they are 450 years old, they were written by men who knew their business and included them in the prayer book for good reason.

The basic rule here is: ‘If you don’t know why you’re doing something at the altar—extravagant elevations of the host and the chalice, for example—stop doing it.’

Most of the priests guilty of such excesses appear to be unaware that such practices are a hangover from the Medieval superstitious belief that the higher the host was elevated, the more effectively it was consecrated.

In those days it was common for worshippers to shout at the moment of consecration: ‘Hoist it higher, Sir John! Hoist it higher!’

Priests in the Middle Ages were considered honorary members of the knightly class and were addressed with the honorific ‘Sir’ rather than today’s more modest ‘Father’, ‘Pastor’, ‘Mister’ or ‘Yo!’

Curiously enough, some of the best liturgical rules come not from the rubrics, or from professors of liturgics for that matter, but from decidedly secular sources.

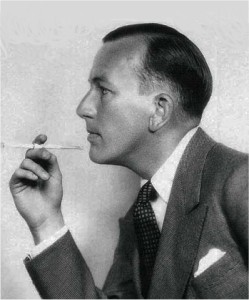

One of the best pieces of liturgical advice comes from the late Noel Coward—one of the 20th Century’s most talented actors and playwrights, affectionately known to his peers as ‘The Master.’Coward’s basic message is found in his comic song ‘Don’t put your daughter on the stage, Mrs Worthington!’ and it should be taken heart by every clergyman. Essentially, it boils down to: ‘Don’t do anything at the altar that looks weird.’

This excellent advice was amplified when a young dancer in the chorus asked him: ‘Master, how does one become a great musical comedy star?’

‘Speak distinctly,’ replied Coward crisply, ‘and don’t bump into the furniture.’

It’s perhaps the must useful tip one could give to anybody serving at the altar—whether priest, deacon, subdeacon, or acolyte. Sad to say, it is advice that is honoured more in omission than observance.

Another secular source of important liturgical advice came from Robert Pocock, an influential poet who served for many years as head of the Poetry Department at the British Broadcasting Corporation’s ultra high brow Third Program.

If I were ever to write a Most Unforgettable Character I Ever Met column for the Reader’s Digest, Bob Pocock would be well up in the running for the title. He was as unlikely a dispenser of liturgical advice as he was an unlikely choice to head a highbrow radio service’s poetry department.

Bob was born in Bristol and came to London as an aspiring poet during the Great Depression. Jobs were in desperately short supply for aspiring poets in those days, so to keep body and soul together, Bob joined the Metropolitan Police Force as a London bobby.

As luck would have it, he was immediately posted to Bloomsbury, the centre of London’s artistic and literary milieu, where his novelty as a policeman/poet made him something of a local celebrity. Naturally, he was wined, dined and feted—occasionally to excess.

One night shortly after midnight, the duty sergeant at the Bloomsbury police station heard a terrible groaning coming from the yard behind the building. On investigating, he discovered Bob dangling, head first, by his trouser turn ups which had been caught in iron spikes embedded in the top of the wall that surrounded the yard.

Bob, an inveterate curfew breaker, had returned from a party to his room at the police station long after the gates to the yard had been locked for the night. Instead of courting certain punishment for being late and less than sober by marching up to the front door, he had attempted to scale the eight foot wall.

Soon after, he and the police department decided to part company, and Bob took his cultural talents off to the recently founded British Broadcasting Corporation. It was an exciting environment for a young and talented poet, and Bob soon made his mark both as a producer of poetry programs and as a ‘voice orchestrater’.

One of his greatest achievements came with his role in the commissioning of the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas’ masterpiece Under Milk Wood, a classic example of voice orchestration. The play for voices, first broadcast by the BBC in 1954, is set in a fictional Welsh fishing village named Llareggub (‘bugger all’ backwards).The characters include blind Captain Cat, reliving his life at sea; Mrs. Ogmore–Pritchard, relentlessly nagging her two dead husbands; Dai Bread with his two wives; Organ Morgan, obsessed with his music; and Polly Garter, pining for her dead lover.

Under Milk Wood had been recorded a number of times since it was first broadcast by the BBC and in 1972 it was filmed with the late Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor in leading roles.

What is the importance of voice orchestration to radio, the church, and any other spoken medium?

Bob explained it this way: ‘It is hard for people to listen to a single voice—even a really pleasing voice like Richard Burton’s—speaking for prolonged periods. Sooner or later they lose concentration, their minds wander, some might even drop off to sleep.

‘In radio we learned early on that to keep people’s attention, we needed to use a variety of voices, especially in documentaries and cultural programs. When voices change often people don’t have so much an opportunity to let their minds wander.

‘It’s why people drop off to sleep in church. It’s usually one chap droning on and on and on …’

So if you wonder why we have all those voices at St Stephen’s altar every Sunday, blame Bob Pocock. We are just trying to save you from nodding off. GPH✠