This monograph is also available as a PDF, suitable for downloading or printing, and reading off-line.

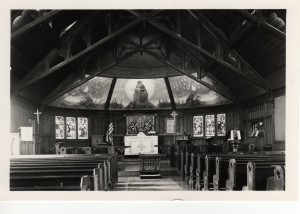

St Stephen’s handsome oak altar originally graced the sanctuary of St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church at Sparrows Point, Maryland. It was presented to the parish in memory of Mary A. Owings, a member of the family that gave its name to Owings Mills, who died in 1891.

St. Matthew’s was built in the latter part of the 19th century to serve the Sparrows Point shipbuilding and ship repair community. And the woodwork of the altar is as much a tribute to the craftsmanship of the shipyard’s carpenters who made it as the young woman it memorializes.Restorers estimate that 32 different woods have gone into the construction of the altar. Both the altar, itself, and its reredos are made of quarter sawn oak—the 19th century shipwright’s basic raw material.

Knotted ship’s cables carved in the oak frame the reredos, which is decorated with an ALPHA and OMEGA made from holly. Some 30 woods were used to compose the delicate marquetry that embellishes the front and both sides of the altar.

A marquetry ALPHA decorates the south side of the altar and is matched by an OMEGA is on the north. The marquetry acrostic at front center of the altar consists of the Greek characters Iota, Chi, Theta, Epsilon, Sigma. They stand for “Jesus Christ, God’s Son, our Savior.”

They also spell icthys, the Greek word for fish—the symbol by which Christians in the days of Roman persecution recognized one another.

Sparrows Point flourished as an industrial center from the latter part of the 19th century until the 1970s. Maryland Steel Company established the Sparrows Point yard in 1889, and it delivered its first ship in 1891.

Bethlehem Steel Corporation acquired the Sparrows Point shipyard in 1917. During the mid-20th century, the Sparrows Point yard was one of the busiest in the country, delivering 116 ships between 1939 and 1946.

During the 1970s, Bethlehem Steel invested millions of dollars in upgrades and improvements to the Sparrows Point facility, including a large graving dock for the construction of supertankers up to 1,200 feet in length and 265,000 gross tons weight.

These “improvements,” however, necessitated the demolition of most of the Sparrow’s Point community, including St. Matthew’s Church. Families who had presented memorial gifts to the church were told to collect them and donate them to their new parish churches. The memorial altar and the stained glass windows were shipped off to other parishes.In 1990, when planning was under way for construction of St. Stephen’s new parish church in Timonium, a founding member, the late Miss Mary Stuart Barnhart, a niece of Mary A. Owings, launched a search for her family altar. It was exactly what the new church needed, she thought.

Mary was told, in no uncertain terms, she was on a fool’s errand. More than 30 years had passed since St. Matthews had been demolished. Nobody knew which parish had been presented with the altar. Indeed, conventional wisdom asserted it had been destroyed.

But Mary was quite implacable. First she traced St. Matthew’s stained glass windows to a church near Bel Air, Maryland. Its rector told her that a silver flagon presented to St. Matthew’s had been given to St. John’s Episcopal Church, Glyndon.

The Rector of St. John’s found the flagon in his sacristy, returned it to Mary, and after cudgeling his brains ventured the suggestion the altar had been given to Rosewood Center, the facility for severely developmentally disabled people run by the State Department of Mental Health and Hygiene.

At Rosewood, Mary struck pay dirt. She discovered the altar in a vast warehouse, which seemed to be a final resting place for damaged and broken equipment. It was in deplorable shape: filthy, with splintered wood and stove in marquetry. “It’s quite beyond repair,” she was told.

But Mary was not so easily discouraged. She had the altar shipped to the workshop of the late Commander Donald Kirk, another of the parish’s founders. Don, a retired U.S. naval officer, was a highly skilled woodworker.

Six months later, he unveiled the altar, fully restored. It had been an extraordinarily difficult task. “The oak was in pretty good condition,” he said, “And it wasn’t too hard to match the holly. The really difficult bit was identifying all the different woods in the marquetry, matching them and putting them back together.”The altar, thus, stands as memorial to a whole host of people: Mary A. Owings, to whom is dedicated; the anonymous 19th–century Sparrows Point shipwrights who conceived and built it; the implacable Mary Stuart Barnhart, who tracked it down; and the irascible Don Kirk, who so painstakingly and lovingly restored it.

May their souls, with the souls of all the faithful departed, through the mercy of God, rest in peace, ✠ and light perpetual shine upon them. AMEN.

Leave a Reply