Parsons are probably more acutely aware of the phenomenon than most people. Three decades ago a congregation would have felt short–changed with a sermon lasting less than 20 minutes. Today, the folks in the pews start fidgeting after a bare 10 minutes.

In short, the average American’s foreshortened attention span appears to correlate directly with the amount of time between the advertisements that punctuate television programs.

Some observers argue that commercial breaks are a boon. They enable viewers to grab a cup of coffee, a snack, or visit the bathroom without missing a second of their favorite soap.

But, from a socio-economic perspective, one is forced to wonder whether the effect of the phenomenon on other aspects of life—education, commerce, government, personal relationships and, yes, worship—are quite as benign.

For the past 30 years, virtually all of the nation’s churches have been wrestling with the problem of the shrinking American attention span. Non-liturgical churches have sought a solution by incorporating elements of pop culture in their services.

Pews have been replaced by cinema seating. Traditional hymnody has given way to rock’n’roll. Sermons have morphed into Power Point presentations, often with sound effects, light shows, and on-stage fireworks. Some preachers have even adapted their services to the TV talk show format.

The response of American evangelicals to this sort of change has been largely positive. But while it is hard to argue with success, it is not a model that can be easily followed by liturgical churches. Shortening sermons is easy enough. Here at St Stephen’s, we have been doing so for the past couple of decades. Arguably, sermons have improved as a consequence. Accommodating the contemporary culture to the same extent as the non-liturgical churches, however, is a horse of quite a different color. Not least, rock’n’roll, Power Point presentations, sound effects, and the TV talk show format are not conducive to the contemplative spirituality the traditional liturgy is intended to inspire.

The traditional Anglican liturgies, moreover, are intended to present worshippers with eternal theological truths. Simplifying these liturgies risks diluting those truths– distorting some and deleting others. What’s more, simplified liturgies tend to sound just a teeny bit silly.

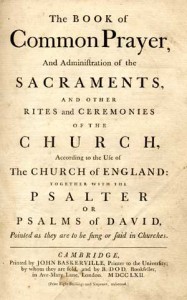

Even so, for the past decade or so, we have noticed not only inquirers, but also the occasional parishioner, remarking on the “wordiness” of the 1928 Eucharist. Perhaps this should not have surprised us. After all, by the year 2000, three decades had passed since the abandonment of the 1928 Book of Common Prayer and the liturgy that had been in use since the early years of the 19th Century.

Few Episcopalians under the age of 50 are familiar with traditional liturgy. Even fewer are acquainted with Morning and Evening Prayer. The Daily Offices fell into disuse in most “progressive” Episcopal parishes during the early 1960s.

Unfamiliarity with the 1928 liturgies presents traditionalist parishes like our own with a problem: How are we to satisfy the demands of a younger generation for a more succinct liturgy, while remaining true to the vision of our founders.

St. Stephen’s is unique among traditionalist parishes in that it was founded 1in 982 by the Baltimore Chapter of the Prayer Book Society of the Episcopal Church. Its express mission is to preserve the liturgy and theology of the traditional Book of Common Prayer.

In an effort to satisfy demands for a more succinct liturgy, we explored “updated” versions of traditional rites, including one developed by the late Rev. Dr. Peter Toon, a former president of the Prayer Book Society. None, however, fitted the bill. Even Dr. Toon’s liturgy seemed “clunky” beside the original—lacking the cadences and internal rhythms of its prose.

This was hardly surprising. It was not so long ago that Thomas Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer, the King James Bible and William Shakespeare’s works were held up throughout the world as the apotheosis of English literary excellence.

The solution to our problem was the 1662 edition of the Book of Common Prayer. It is, funnily enough, a remarkably modern liturgy—simple, straightforward and economical. The 1928 Eucharist, by contrast, tends to be complex, prolix, and repetitive, incorporating both of the long post communion thanksgiving prayers designated as alternatives in the 1662 Rite.

It is, moreover, more logical in structure than the 1928 Rite. The Prayer of Humble Access, for example, precedes the Prayer of Consecration. In the 1928 Rite, it precedes the distribution of consecrated elements.

While neither position is “wrong” per se, Cranmer’s placement of the Prayer of Humble Access is preferable because it emphasizes that because of our sinful nature we are not even worthy to celebrate the Eucharist, let alone receive Christ’s Body and Blood.

In any event, the 1662 Rite is between 10 to 15 minutes shorter than the 1928 version. Brevity in worship is not necessarily a virtue. But the verbal economy and logical order of the 1662 make it more accessible to newcomers while sacrificing none of the essentials so beloved of traditionalists. GPH✠

Nicely written and timely. Thank you

My understanding is that « traditional Anglican Liturgies » in the United States of America from 1607 would have been the English Book of Common Prayer 1552, which was followed by the edition of 1662. This was revised in 1789, in 1892 and in 1928 in the Protestant Episcopal Church of the United States of America.

This morning I used the “l’Association Épiscopale Liturgique pour les pays Francophones » form of Laudes, which on Sundays is called Matin. I could have used the Book of Common Prayer 1662 in English or French 1863, or in Bengali or Hindi 1962, but all of those seem exotic in my situation and so I use what the locals use.

Sentiment is attached to old forms, and so I find comfort in saying the “Notre père qui es au cieux” when by myself in the English 1662 form or the Bengali 1962 form. At Peterborough Cathedral for a weekday Holy Communion, some years ago, I found myself saying, “Je ne suis pas digne de te recevoir…” a version of the English Prayer of Humble Access.

However in my forty four years of ministry in six parishes in three languages, I only ever had one request for 1662, “the language of Shakespeare” which of course it is not. The person never attended Church, so 1662 gradually lost use.

The problem is that use of language changes, and that makes old forms difficult to use, so there has to be revision from time to time. Today there is anxiety to get closer to the ancient forms and avoid medieval excrescences, and the form most favoured is that of the Apostolic Tradition by Saint Hippolytus. A look at the Jewish Hebrew Forms will show how short and straight to the point they are. I do not think that the Traditional Forms grounded in the Middle Ages could be called that.