Folks familiar with Church history usually claim the first English Prayer Book is the First Prayer Book of King Edward VI, which was authorized for use in 1549. True, this wonderful book is the ancestor of all the Books of Common Prayer in use in the world of Anglicanism today—albeit a very distant one in many cases, with its literary and theological DNA scarcely discernible. But it cannot fairly be claimed that it is the English Church’s first prayer book.

The English Church has played a major role in the liturgical life of the Church catholic for more than one and a half millennia. Yet most Anglicans are entirely ignorant of the fact. This year’s Lenten Study will trace the development of the BCP from pre-Saxon times onwards.Our Lenten Series “The Development of the Prayer Book” runs for five Wednesday evenings beginning after 6:00 PM Evening Prayer on February 20th and ending on March 20th. The presenter will be the Rector.

We are offering the usual deal—a hearty winter soup, the best bread in Baltimore and beverages. If you need more to eat, you are welcome to bring a sandwich.

There will be plenty of food for thought: The liturgical works that survive from times prior to the Seventh Century demonstrate a lively liturgical tradition in which much, if not all, of the Eucharistic rite was celebrated in the vernacular rather than Latin. Thus it can be claimed they were distinctly English liturgies.

Latin, however, was the ingua franca of the polyglot British society, which by the 6th & 7th Centuries embraced a number of languages, including at least three major strains of Gaelic (four, if you include Pictish), Anglo Saxon and Old Nordic, and numerous dialects of each.

When it came to the written word, Latin was a convenient compromise in an age when books, even of the cheapest sort, were laboriously hand copied by scribes. But while service books were often written in Latin, it was the custom for celebrants to make a running translation of the liturgy into the vernacular—a practice continued by priests today in places, such as the Philippines, which boast multiple languages.

You’ll find evidence of this practice, for example in the autobiography of Ireland’s patron saint. In his Confessions, written in the late 5th/early 6th centuries, St. Patrick grumbles that his native Latin has been ruined by years of speaking the “barbarous” Irish tongue. His Confessions show he wasn’t exaggerating. Patrick’s Latin is, indeed, execrable—far worse than one would expect of a priest who routinely celebrated in Latin.

By the way, this habit of saying the liturgy at least partially in the vernacular seems to have continued into the early Middle Ages when the Epistle and Gospel were often read in the vernacular during parochial Masses. And it’s worth noting that Archbishop Thomas Cranmer re-instituted this practice as a temporary measure before the 1549 Prayer Book was authorized.Latin, however, did not entirely displace the major local languages as the medium for religious publishing in Britain until late in the first Millennium. A considerable body of writings remains from the ancient church in Wales and Ireland; while among the towering literary achievements of the pre-Norman English Church in the 8th Century was the Venerable Bede’s translation of the Gospels into Anglo-Saxon.

The great historian and scholar, who spent virtually his entire life at the great Monastery at Jarrow, is best known today for his History of the English Church and People. But tradition has it that his last words were those of the final verse of St. John’s Gospel:

“And there are also many other things which Jesus did, the which, if they should be written every one, I suppose that even the world itself could not contain the books that should be written. Amen.” Then, having completed his self-appointed task, he begged for the Gloria in Excelcis to be sung and, as the brother sung the great hymn, Bede died.

Contrary to common belief, England from the late 6th Century to the early part of the 9th Century was among the most prosperous and relatively tranquil places in the West. Europe, as St. Martin of Tours records, was wracked by constant warfare. Northern and central Italy was laid waste by barbarians. Rome had been put to sack not only by the barbarian invaders, but its own unpaid soldiery. Sicily had been conquered by Moslem hordes, who used it as a base to invade southern Italy and threaten Rome itself.

But with the rise of the Frankish Empire in the mid-8th Century, the situation began to stabilize. Charles or Karl, the Frankish king, was later proclaimed the Holy Roman Emperor. Charlemagne, as he came to be known, was not content to remain a semi-barbarian tribal leader—a Franco-German Attila the Hun.

He transformed the Palace School at his court in Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle)—founded by his ancestors to teach royal children manners—into a center for the study of religion and the liberal arts. And the man he chose to lead it was a disciple of the Venerable Bede, an eminent English scholar named Alcuin from St. Peter’s School at York, renowned as a centre of learning not only in religious matters but also in the liberal arts, literature, and science.

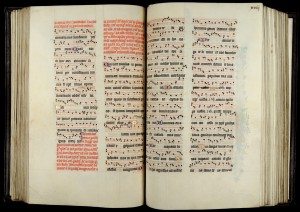

A Sarum Missal, dated around 1418. A mention of the Pope in the far right column has been scratched out by order of Henry VIII. (Via Modern Medievalism. The photograph is from the Bridwell Special Collection at SMU.)

In the course of doing so, he—unintentionally perhaps—preserved for future generations the works of ancient Rome’s literary giants (Virgil, Livy, Cicero, Ovid, Tacitus, Horace, Terence, Martial, etc.). Alcuin, you see, insisted his apprentice scribes perfect their skills on secular writings before being permitted to tackle the sacred.

More relevant to the subject under discussion, Charlemagne considered the Eucharistic liturgy in use by the Roman pontiff too simple and primitive for use in an emperor’s court. Thus he commissioned Alcuin to compose the Eucharistic liturgy for the Holy Roman Empire.

Ironically perhaps, until the Counter Reformation which began in the mid-16th Century, the Mass said by the Roman pontiffs was a rite essentially inspired by the Rite of York—one of the great English pre-reformation liturgies. Even more ironically, the Mass that emerged from the counter-reformation was largely derived from the Sarum Rite, the oldest of the English Eucharistic rites. Come and find out about it on Wednesday, February 20th, at about 6:45 PM. We guarantee you won’t be bored! GPH✠